By Maya Indira Ganesh, 8 April 2014

When Viktor Yanukovych fled Kiev, he dumped a lot of incriminating paper documents into the lake on his lavish property. Shortly after, investigative journalists brought in divers who retrieved the documents, used hair dryers to dry them and then scanned them as .pdfs for future examination. Amongst the retrieved documents were receipts for Yanukovych's spending, names of blacklisted journalists and so on.

Technologies to retrieve, categorise, digitise and store the data embedded in these soggy paper documents are now accessible through investigative data journalism networks inspired and supported by people like Paul Radu. Radu's work and that of his organisation, the Organised Crime & Corruption Reporting Project, helps investigators and journalists locate, digitise and analyse evidence of corruption. Much of this evidence tends to be 'locked' in formats difficult to acess: paper records, .pdf files, guarded offshore tax havens and money-laundering operations with fake front companies (learn more about how this happens, in Paul's own words, here). While Yanukovych's corruption is neither secret nor a revelation, these technologies will be used to verify the scale and specifics of it - hard data as evidence - which may be used in legal action against him in the future.

(Image from www.kyivpost.com)

There is something heroic in this story: investigative journalists brandishing hairdryers, underwater divers and ultimately, the incriminating data itself. Some would like to be cautious and coy in their appraisal of technology in transparency and human rights, but let's face it, there's a bit of a super-hero feeling all around. From life-hacking to corruption-exposing and violence-predicting to dictatorship-dismantling, data is a sort of superhero in advocacy and technology-driven social change. While data has always been integral to campaigning, the current information technology eco-system we're operating in means that there is renewed interest in and focus on how new capacities can be brought to bear on human development and social justice.

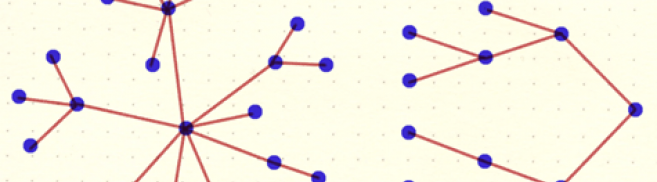

But back to Ukraine. Many believe that activist networks, people-power and citizen action were instrumental in driving the national protests that got Yanukovych out. However, a recent predictive data modelling study suggests that it is not people-power necessarily, but the increase in food prices that is actually pushing people to protest in different countries. This model predicted riots in Brazil, Thailand, Venezuela as well – all of which have indeed erupted:

"The paper's author, Yaneer Bar-Yam, charted the rise in the FAO food price index—a measure the UN uses to map the cost of food over time—and found that whenever it rose above 210, riots broke out worldwide. It happened in 2008 after the economic collapse, and again in 2011, when a Tunisian street vendor who could no longer feed his family set himself on fire in protest. Bar-Yam built a model with the data, which then predicted that something like the Arab Spring would ensue just weeks before it did. Four days before Mohammed Bouazizi's self-immolation helped ignite the revolution that would spread across the region, NECSI submitted a government report that highlighted the risk that rising food prices posed to global stability. Now, the model has once again proven prescient—2013 saw the third-highest food prices on record, and that's when the seeds for the conflicts across the world were sown."

What a dampener for advocates of activism and citizen agency! While local events tend to be complex in origin and emerge from a weaving together of many factors, where you're located will determine how you tell the story of change.

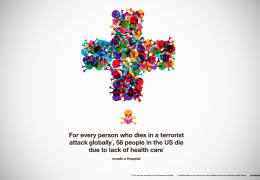

Data-gazing is becoming popular. There was a recent story in the New York Times about how big data – from hate speech on Twitter to infant mortality rates – is being mined and analysed to predict large scale violence. According to the story, some universities are developing computer programmes that process diverse datasets looking for patterns about factors that could work together to result in violence in different parts of the world, including the Central African Republic (CAR), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Syria, all of which have come to pass.

In the Hollywood version of large scale destruction in a super-hero movie, they never show you who cleans up Gotham City, how they haul away all the damaged vehicles and who puts the glass back in the broken windows. So prediction is all very well, but it isn't clear yet what these developments mean for how states actually respond to large scale violence; how accountability will be claimed; and what if the state itself enacts violence on its people? If these predictions are going to guide political will and the allocation of public resources then they should be transparent, comprehensible and wielded by people who have the competence to do so. Transparency is highly unlikely in a scenario that involves national security: secrecy is the norm for any sort of security advantage.

(Cartoon by Ed Stein, 2006 from www.blogs.rockymountainnews.com)

Given how big data techniques have hollowed out our personal lives with little policy or legal oversight, what can we expect from states who access and use this kind of data? Who are the cadre of competent people who will use the data capacities that exist to develop the policies we need? How will big data predictions be used in the service of realpolitik in cases like Syria, CAR or other disasters to avoid responsibility, action or blame - a 'the numbers didn't suggest that action was feasible' scenario?

These sorts of questions will have to come later because, as Chris Anderson writes, the age of Petabytes teaches us that we must think of data as mathematics first and context later. He uses Google as an analogy:

"Google conquered the advertising world with nothing more than applied mathematics. Google's founding philosophy is that we don't know why this page is better than that one: If the statistics of incoming links say it is, that's good enough. No semantic or causal analysis is required. That's why Google can translate languages without actually 'knowing' them (given equal corpus data, Google can translate Klingon into Farsi as easily as it can translate French into German). And why it can match ads to content without any knowledge or assumptions about the ads or the content."

The capacity to predict genocidal violence is having a discursive influence on how interpersonal violence will also be addressed. With the conclusion of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) annual meeting at the United Nations in New York in March, the MDGs, or Millennium Development Goals, set to be achieved by 2015, were criticised for not being able to generate social transformation, particularly women's empowerment. The MDGs did not build in women's empowerment measures as expected outcomes, and drivers, of social change.

Now, violence against women is (finally) being recognised as an indicator of women's disempowerment. The UN conceded that the social norms that drive women's disempowerment and gender based discrimination are too complex to measure comprehensively, which was making it difficult to come up with these indicators of women's empowerment in the first place. However the ODI ( Overseas Development Institute ) and the OECD ( Organisation of Countries for Economic Cooperation and Development), have found ways to use existing data to develop six new indicators for women's and girls' empowerment using stronger statistical data collection systems. As a result, there will be more emphasis on the collection and rigour of data on gender-based violence and women's empowerment.

Last week I spent the day in Istanbul with Civicus and the Engine Room who had convened a group of women's rights activists to give them some insights into how citizen-led data projects, in this case about violence against women, could be 'harmonised' and thereby leveraged for 'people-powered accountability'. Civicus hopes to take the lead in supporting citizens to hold governments to account in the achievement of the SDG measures.

The reality of a women's rights organisation pulling together information to document violence is tough and full of challenges and at the same time is really inspiring to see in action. It is about bottom-up knowledge production, rich in insights and bringing voice and agency to communities. Unfortunately, the most visible examples of this are not necessarily the most rigorous, comprehensive or insightful; nor are all kinds of violence the same, obviously. So, it is unikely that documenting street-based sexual harassment will have any implications for the rates of violence that happens in the private sphere, like domestic violence or child sexual abuse, which are what the indicators that measure women's empowerment are based on. (Though who wouldn't love the idea that increased visibilty and attention to the problem of violence actually inspired change for women in the home and family).

These 'other violences' are actually quietly being counted, recorded and have been for years, but far from the glare bouncing off of new technologies. Some of these are large epidemiological studies across countries, others are smaller, independent researches and reports. Many are in difficult formats too - different languages, a mix of qualitative and quantitative, in .pdf files, case studies. There is a role yet to be clearly scripted in how citizen-led reporting and local research on violence acts as the 'thick data' that Tricia Wang says must bear on bigger data, how it can be harmonised as the Engine Room asks, genuinely fills in the contextual gaps and offers information-rich narratives as alternatives to the dominant one.

And here is a chilling thought along the lines of a 'Majority Report': data-based predictions of sexual violence developed in order to prevent it, much like the genocide predictions. This is really not that extreme an idea; in the documentary film Terms and Conditions May Apply, a happily married novelist is suspected of plotting to kill his wife based on his detailed online research into murder methods, which was obviously for his next novel. ('Rape fantasy' is a legitimate porn category). The privacy implications of this could fill a textbook.

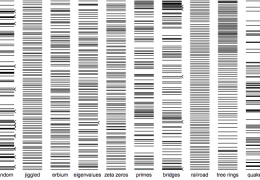

So here's the conundrum at the heart of data-gazing. There is a sort of super-power in data to tell the 'truth' ruthlessly and unflinchingly; this super-power is its supposed rigour. And yet, the predictive arts are some of the most easily derided for being 'irrational', un-representative and not based on any 'hard' data or rigour. Anyone who has looked at the horoscope section furtively knows what this means.

Earlier in this series, Mushon Zer-Aviv talked about how data can be manipulated to lie and in the next post is about how the social production of data skews results in counting violence on a large scale. There is a lot of power in being able to look back and look ahead in order to know the trajectories and outcomes of social events. There are, however, many ways of seeing.

Header image by Maya Ganesh, view of Truc Bach Lake, Ha Noi, 2009

*With thanks to Tom Longley for additional words and ideas.

Maya is the Evidence & Action Programme Director at Tactical Tech.