By Maya Ganesh 16 April 2015

This two-part post closes a series on this blog about the dilemmas of data in advocacy. The first post uses two cases to show how data is generated and deployed as a way of 'knowing' the 'problem' of trafficking; and how it serves as a rationale, then, for specific interventions to control trafficking. The next post is a series of reflections and practical learnings from a project we did with a Cambodian sex worker collective that was about 'small data' and building a community's capacity to own and generate data about themselves.

Trafficking is the local and international movement of people for sex-work, as human organ donors, migrant or bonded labour and (usually illegal) immigrants; of drugs ('drug trafficking'); human organs ('organ trafficking'); and weapons ('arms trafficking'). Victims of trafficking for sex come from a diversity of backgrounds and include displaced or stateless people, job seekers, tourists, sex-workers, runaway teens, drug addicts, refugees and so on. Human trafficking, and particularly sex trafficking and the trafficking of children, are criminalized under various human rights instruments.

A distinctive aspect of trafficking that its Wikipedia page will testify to as well: statistics about how many people are trafficked across the world are highly contested, and ironically, it is these contested and contentious statistics that form the basis of policy. Two stories, one from Asia and the other from Europe, show how this plays out.

Cambodia

By day, traffic orbits the Independence Monument at the south end of Phnom Penh in big, lazy loops; at dusk, groups of teenagers, and old people practicing t'ai chi flock to the gardens in front of it; and at night, it is a busy sex-work zone. Ever since the Cambodian government passed the Anti-trafficking Law in 2008, the national monument in Toul Kok district has become one of many sites of regular raids where sex-workers are picked up for detention and arrest.

The Anti-Trafficking law was passed to check the trafficking of migrant labour into and through Cambodia but has ended up giving local police powers to arbitrarily stop and arrest sex workers, the assumption being that a sex-worker must have been trafficked rather than chosen this profession. Sex workers have told us that police will arrest women because they are carrying condoms, the assumption being that only sex-workers carry condoms in their purses – and even if they are not soliciting customers!

Cambodian sex workers talk about the impact of the anti-trafficking law

How and why the Anti-trafficking Law in Cambodia came to be passed is a story about data – highly contested and contentious data. During George W. Bush's administration, non-humanitarian and non-trade related aid was contingent on a number of factors such as the recipient country's record on trafficking and an 'anti prostitution pledge'. Cambodia is also a significant recipient of US aid. The Cambodian government was downgraded on the US' Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP), a yearly report authored by the Central Intelligence Agency, amongst other government agencies, for not taking strong enough measures to eliminate trafficking into and through the country. (Read a critical perspective on TIP reports here). In 2003 Cambodia was given a low rating on that year's TIP Report.

So, in 2008, the Cambodian government, under pressure from the United States (as described by Sandy in Labour, Migration and Human Trafficking in South East Asia: Critical Perspectives here) , enacted a law to regulate human trafficking into and through the country. Estimates from 2001 suggested that 80,000-100,000 women and 5000-15000 children in Cambodia had been trafficked into sex work. These numbers were estimated on the basis of [mostly anecdotal] NGO reports about how big they thought the problem was.

This number somehow surfaced in the UNDP's Cambodia Human Development Report (2000) as the number of sex workers in the country. As a result, there was a conflation between sex work and trafficking, which are actually two very different things, and the connection between them is made on the basis of ideology and morality, rather than reality. (This is true in most parts of the world, not just in Cambodia). So, there was a significant inflation of the rates of trafficking coming out of Cambodia. Reports like this had everything to do with the US' low rating of Cambodia in the TIP Report. In order to combat the 'alarming' levels of trafficking in Cambodia, the anti-trafficking law was passed.

However, in 2003, one study challenged the prevailing numbers; the study asked a very different and pertinent question about what trafficking actually is: the conditions of financial servitude and exchange that trafficked persons are subject to, rather than investigate the muddied trails of people in transit. As a result a dramatically lower figure emerged: 20,000. Thomas Steinfatt, the lead researcher of the 2003 study, went on to publish another report in 2011 that summarised the flaws in all the prior research on trafficking in Cambodia by showing how the wrong questions were asked about trafficking. In doing so, they exposed the flimsy basis for the anti-trafficking law in Cambodia.

In another instance, Cambodian activists worked with a range of local agencies, including the national HIV / AIDS agency, CACHA, to sample a small population about their experiences of trafficking and the sex industry and show how the law was being used to regulate 'entertainment workers', less than 1% of who had actually been trafficked (this study is cited here, and the link to the actual study is broken)

Europe

A very different sort of data story has been playing out in Europe, in which data is being generated about trafficked persons through sophisticated systems of surveillance, tracking and monitoring.

Bärbel Uhl is a German advocate working with anti-trafficking groups in Europe. She is also one of the founders of La Strada International, an Amsterdam-based sex worker rights and advocacy group. Uhl is one of the few people doing critical, original research on data protection in the context of sex-workers' and trafficked people's rights.

Bärbel's project datACT engages in research, training and public debates to promote the rights of trafficked persons to privacy, autonomy and the protection of their personal data. Their work seeks to critically analyse these procedures against European data protection standards in order to strengthen the rights of trafficked persons as 'data subjects'.

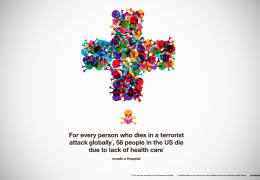

Bärbel supplies an analogy to describe the scale of data collection about trafficked persons and its usage. Anti-terrorism and anti-trafficking are two areas where, in the name of prevention, vast amounts of data are collected about people who cross borders. However, she says, “in anti-terrorism everyone is obsessed with potential perpetrators, but in anti-trafficking they are obsessed with victims.” It is one of those rare crimes where more information is collected about victims than about perpetrators; if they are really serious about ending trafficking then why aren't there databases about perpetrators?” she asks.

Recent changes in EU directives and policies to combat trafficking have made data collection central to the effort of monitoring migration and trafficking in Europe. Bärbel rattles off a string of acronyms and abbreviations- IOM, ICMPD, Euro-Sur, Euro Stat – of organisations and registers in Europe that collect and process data about trafficked people. She contends that trafficking as a human rights issue has actually made it easier to (uncritically) allow for data collection as a means to know the scope and scale of the problem and to look for answers ostensibly about how to deal with it.

She talks about the big new database called Euro-Sur ('Europe-Surveillance') that is an example of Europe's new 'smart borders' system, where databases become the interface through which the state regulates citizens and 'others'. There is the International Organisation on Migration (IOM) that maintains a vast database on sex trafficking including personal details about sex worker's sexual history and exploitation. The International Centre on Migration Policy Development has a similar database about victims of trafficking.

In the United States, Palantir Technologies, a big data infrastructure and analytics firms associated with the CIA, does 'philanthropic' work for NGOs and non-profits. They work with the Polaris Project, managing data from their national helpline for trafficked and exploited people. What are the implications of an organisation with this sort of access being involved with sensitive data about some of the world's most marginalised people? The answer is hard to stomach.

One of the reasons why there is more data about sex-workers and trafficked people is possibly because of the relative powerlessness of trafficked people; and that by regulating their bodies, there is a perception that the broader problem is being regulated, when in fact this is not necessarily the case. Further, organisations in Europe working with sex-workers and trafficked people do not even have the right to refuse to testify in courts of law against their own clients based on the data collected about them. Bärbel's suggestion in the age of multiple, interlinked databases – radically revise the data you collect about trafficked people and recognise the need for privacy. Just because we can collect data, should we be collecting all of it?

The Polaris Project talks about how Palantir Technologies help them manage their data on trafficking.

This post was written by Maya Indira Ganesh, Tactical Tech's Research Director. It draws on our work and association with sex worker rights activists and collectives in Cambodia from 2010-2012, and interviews with Bärbel Heide Uhl of DatAct in Berlin, Germany, in 2013-2014. Many thanks to Pisey Ly, Ros Sokunthy and Bärbel Uhl.